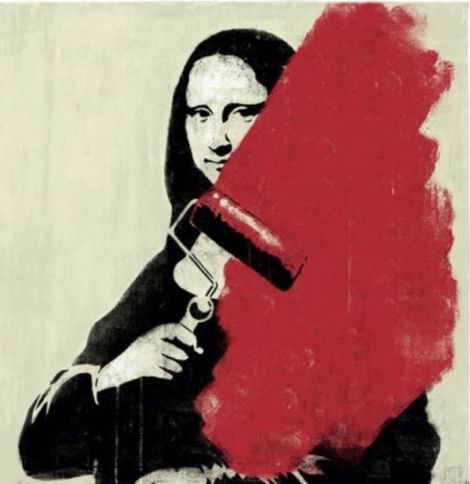

Madonna in de kerk

Dit olieverfpaneel van Jan Van Eyck heet tegenwoordig ‘Maria met kind in een kerk’. Het werd vermoedelijk vervaardigd omstreeks 1440. In Mystiek lichaam, de bekende roman van Frans Kellendonk uit 1986, wordt het schilderij uitvoerig beschreven. Het vormt een opmerkelijk directe referentie aan de buitenliteraire werkelijkheid in een alles behalve realistische roman. In Mystiek lichaam heet het paneel ‘Madonna in de kerk’. Het fungeert voor het personage Leendert Gijselhart, kunstcriticus te New York in de jaren tachtig van de vorige eeuw, als absoluut ideaal.

De Madonna in de kerk is Leenderts ‘schilderij der schilderijen’. De gotische kerk symboliseert de wereld van de kunst waarin Leendert zijn heil heeft gezocht. De kerk bestaat ter meerdere eer en glorie van de maagd Maria, het icoon waarin het hemelse – en tegelijk vleselijke – via de kunst zichtbaar wordt. In de woorden van Leendert:

‘De pilaren streven verticaal ten hemel, maar in de transcendente hoogten van de kerk buigen ze zich – voor de maagd, die in het schip van de kerk staat, speciosior sole, met de heiland op haar arm en alle sterren van de hemel in haar kroon. Ze is wel zes meter hoog, die maagd, en ze is van vlees en bloed.’

Leendert beschrijft hier de wonderlijke verhoudingen in het schilderij. De figuur van Maria lijkt namelijk enorm in vergelijking tot het omringende kerkelijke interieur, in ieder geval hoger dan de bogen naast haar. Ze zal haar hoofd hebben moeten buigen wanneer ze via de zijbeuken het schip was binnengekomen. Enkele letters van het in bovenstaand fragment genoemde ‘speciosior sole’ vallen te herkennen in de zoom van haar rode jurk. Een verwijzing naar het citaat Est enim haec speciosior sole uit het Bijbelboek Wijsheid, in schoonheid overtreft ze de zon.

Opvallend is de verbinding die Leendert aanbrengt tussen het transcendentale en het aardse en lichamelijke. De maagd is ‘van vlees en bloed’. In deze verzoenende tegenstelling van het schilderij echoot de oorspronkelijke opvatting van het religieuze icoon, dat werd opgevat als een raam naar het goddelijke. Het icoon aan de muur fungeerde in huis letterlijk als een doorkijkje naar het koninkrijk Gods.

Anderzijds klinkt in Leenderts beschrijving van het schilderij ook de poëtica van Kellendonk door waarin het gekunstelde of de verbeelding de enige weg is naar een oprechte weergave. De reden waarom Leendert het schilderij adoreert is omdat het voor hem laat zien ‘dat het vlees eerst verf moet worden, wil het triomferen. Alleen de kunst kan het vlees over de kunst laten zegevieren’. Via het prisma van de kunst wordt de werkelijkheid werkelijker, of zoals Viktor Shklovsky het zo beeldend beschreef in Art as Technique (1917) ‘art exists that one may recover the sensation of life; it exists to make one feel things, to make the stone stony’. Ik moest aan deze uitspraak van Shklovsky denken bij de terloopse verwijzing naar het werk van Gerard Terborch (1617-1681) even later in Mystiek lichaam, wanneer Leendert beschrijft hoe zijn terminaal zieke partner (de ‘rijpere jongen’) in de lakens hangt. Terborch was bekend vanwege zijn precieze stofuitdrukking, in sommige schilderijen – zoals bijvoorbeeld ‘De brief’ – tot perfectie verheven. De lakens van de rijpere jongen gaan dankzij de referentie aan Terborch glanzen als de jurk van zijn brieflezeres. Stof wordt stoffelijker.

Principiëler zou Kellendonk in zijn essay ‘Idolen’ (1986) concluderen dat het idee van een objectief waarneembare werkelijkheid een illusie is, de wereld die we menen waar te nemen is namelijk altijd een projectie van onze waarneming. Wat dat betreft bestaat er weinig verschil ‘tussen de exacte wetenschappen enerzijds en anderzijds de religie, de metafysica, de kunst’. Voor al die gebieden geldt dat de werkelijkheid niet kenbaar is zonder bemiddeling van de verbeelding.

Hoewel de kunst het geprivilegieerde terrein lijkt als het op de kracht van de verbeelding aankomt, schiet het in de praktijk toch ook vaak tekort. Dit blijkt bijvoorbeeld wanneer Leendert zijn geliefde schilderij, dat hij slechts van reproducties kent, eindelijk in het echt gaat bekijken in Berlijn. Het is een teleurstellende ervaring, want de zes meter hoge maagd blijkt niet groter dan 18 centimeter. ‘Als het niet in een vitrine had gestaan had hij het zonder veel moeite in zijn zak kunnen steken, zo klein was het.’

Niet alleen de pietepeuterige afmetingen van het werk ridiculiseren Leenderts hooggestemde idealen. Het feit dat hij zijn opvattingen over ‘het schilderij der schilderijen’ baseert op een reproductie doet dit misschien nog wel meer. Het valt mij nu pas op, na zoveelste herlezing van Mystiek lichaam, dat de vindplaats van de reproductie nauwkeurig wordt beschreven. Wanneer Leendert als jonge jongen rondsnuffelt op de zolder van het ouderlijk huis, treft hij een afbeelding van het paneel in ‘een ingebonden jaargang’ van ‘een oud maandblad’. Uit de vermelding van de ‘stoffige’ namen in het colofon – Emmy van Lokhorst, prof. Julius Röntgen, Henri van Booven – blijkt dat het gaat om een jaargang van Elseviers Geïllustreerd Maandschrift (1891-1940). Weliswaar een sjieke uitgave, maar de reproductietechnieken van toen waren beperkt en van kleurafbeeldingen was al helemaal geen sprake. Het verband tussen ideaal en werkelijkheid schiet met deze verwijzing verder uit het lood.

Het motief van de reproductie valt overigens al subtiel terug te vinden in Van Eyck’s ‘Maria met kind in een kerk’. Als je goed kijkt, zie je dat er in een nis vlak achter de maagd van ‘vlees een bloed’ een kleiner Mariabeeld met kind staat.

In een recente post op LitHub vraagt Joe Mungo Reed zich af wat een schrijver bezielt om een bestaand schilderij op te nemen in een roman. Volgens Reed symboliseert het kunstwerk in de roman vaak een object van verlangen, ‘a thing that one person has and another wants, which thus puts into motion a whole clanking apparatus of fictional machinery.’ Dit gaat zeker op voor Kellendonks beschrijving van Van Eycks paneel in Mystiek lichaam, dat voor Leendert onmiskenbaar een object van verlangen is, een verlangen naar betekenis voorbij het individu, voorbij het materiële, voorbij het eindige, aardse leven zelf.

Wanneer goed uitgevoerd, geeft de beschrijving van het kunstwerk volgens Reed bovendien ‘fullness to a piece of fiction, indicating the wonders of the world beyond, obscuring the boundary between fictional reality and our own.’ Inderdaad betreft de beschrijving van Van Eycks paneel op het eerste gezicht een duidelijk traceerbare referentie aan de werkelijkheid, waardoor het verhaal – en het personage Leendert in dit geval – aan de realiteit wordt gekoppeld. Gaan we de referentie echter volgen dan blijkt het de lezer juist verder van de werkelijkheid af te leiden. Het tegenovergestelde gebeurt van wat Reed opmerkt; je wordt steeds dieper meegevoerd in de verbeelding.

De beschrijving van ‘Madonna in de kerk’ uit Mystiek lichaam doet precies wat Leendert verwacht van kunst, het laat je opnieuw kijken, opnieuw zien, echter niet naar de werkelijkheid, maar naar de kunst zelf. Van Eycks paneel is na lezing van Mystiek lichaam nooit meer hetzelfde.

—

Mystiek lichaam herlas ik voor het seminar Letterkunde van de Open Universiteit over ‘familieromans’, georganiseerd op 1 april te Utrecht.